Revisiting S-Curves

Rethinking S-Curves has been on my mind lately. One of the most enjoyable parts of my work at the Agile Strategy Lab is working with Strategic Doing practitioners who are taking our online course to become certified as workshop leaders. The course involves planning and executing a workshop with the follow-up needed, documenting the process as they go.

The assignment that makes many of the participants anxious is to record themselves doing an overview of the process – a brief introduction for a group that hasn’t been in a workshop before. While watching the videos can admittedly get a bit tedious, I always pick up new ideas I can use in my own work. One of those last week was a participant’s explanation of the S-Curve.

What’s an S-Curve?

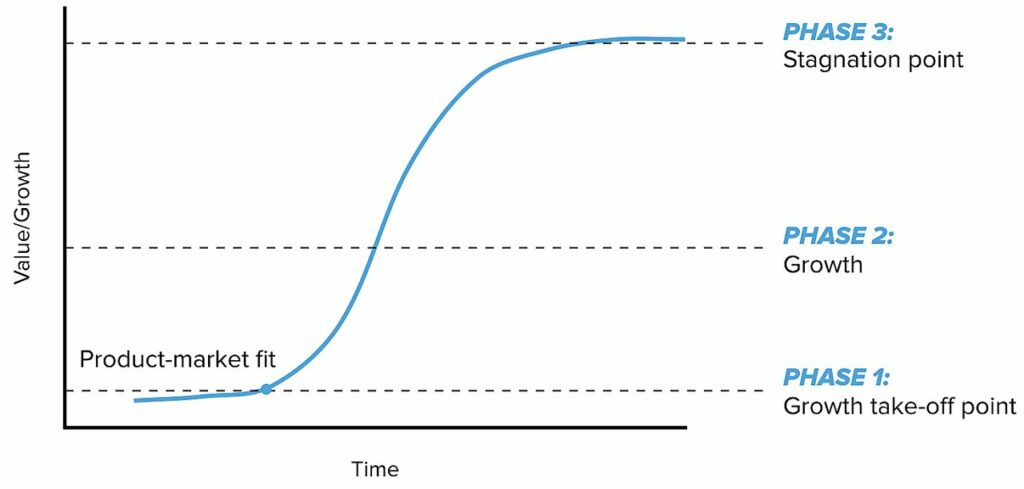

An S-Curve is a graphic representation of the natural life cycle of many things in our world: populations, viral infection rates, local economies, and product innovations. The core idea is that life starts slowly and not particularly productive, picks up steam, hits a plateau of maturity and then declines (although we like to ignore that last part, as many illustrations including this one reflect):

(Credit: Dries Buytaert, Creative Commons license)

S-Curves are interesting on their own (once you grasp the idea, you’re apt to see them everywhere you look), but an extension of the S-Curve idea is that they exist in series. That is, as one S-Curve is in decline, there’s another one ascending. This is where one of our course participants, Kristin Henkaline from Ohio State University, comes in. She credits the Strategic Doing book for this example about landline telephones, but she does a much better job than we did explaining it:

You start off with this new technology – and then it starts to grow. More and more people are using it, and the phones get fancier and fancier. The next thing you know you have landlines where the phone doesn’t have a cord anymore. And we have voicemail attached to it. It does all these things…but eventually the innovation only goes as far as it can go. It starts to plateau – there’s not much more than can be done with that particular innovation. So then what? You have to innovate – you have to think about how you can take all of your resources and use them in a different way to come up with something new: cell phones! It’s this new innovation that’s doing something completely different but also giving us what we needed with our old phones.

The cellphone is the next S-Curve in the series. It’s new in some fundamental way, and yet it builds on what came before.

Why are S-Curves important?

The reason S-Curves are one of the first ideas we introduce in Strategic Doing is that when organizations, institutions, companies, communities find themselves in a place where things aren’t going well, often it’s an S-Curve issue. What’s worked before has gone as far as it can, and something new needs to take its place. Sometimes the new is already taking its place but we haven’t recognized it yet, even if we are very, very smart:

“I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

That was Thomas Watson, president of IBM, in 1943.

Responding to S-Curves

Once we see the S-Curve issue, then what? That’s where Strategic Doing provides value: it gives groups a process, a common vocabulary, and perhaps most importantly a new mindset to interpret what’s happening and chart a course forward together, even when what the new S-Curve will look like isn’t entirely clear and it’s tempting to ignore the coming changes. We can help you learn the process in one of our practitioner trainings. Or, if you’d like to skip right to a workshop, we can help with that too.

Liz shepherds the expansion of the Lab’s programming and partnerships with other universities interested in deploying agile strategy tools. A co-author of Strategic Doing: 10 Skills for Agile Leadership, she also focuses on the development and growth of innovation and STEM education ecosystems, new tool development, and teaching Strategic Doing.