Accelerating University Innovation

For decades, the ground underneath our universities has been shifting. Universities have been slow to respond. Yet, transformation is clearly on the horizon. as our political economy evolves, universities adapt. In his Jonathan Cole notes in his book, The Great American University, “the history of universities in America is inextricably bound up with the history of America itself.”

Alarms Start Sounding in the 1990s

In 1990, Ernest Boyer, President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, wrote a provocative report, Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Boyer challenged traditional notions of scholarship. He proposed some major rethinking. First, he suggested that universities embrace a “scholarship of integration” to move across disciplinary boundaries. Boyer also proposed a new “scholarship of application”, later called a scholarship of engagement.

In 1995, Mary Walshok, a young scholar, pointed to a pathway ahead for universities. They could shape new “communities of discourse” to bridge the gap between abstract knowledge and action-centered scholarship.

Also in 1995, Donald Schön, a professor at MIT, argued convincingly for a new epistemology within the university, one that embraced developing better solutions to the problems found in the “swampy lowlands” of real-world problems.

In 1999, the Kellogg Commission took up the challenge by reviewing how land-grant universities should respond. Some universities began exploring changes in how they reward faculty. Some, for example, marked a path forward for young scholars interested in the scholarship of engagement.

Exploring this path, the 1990s saw new research streams open define “entrepreneurial universities“, “engaged scholarship”, and a “triple helix” model of university engagement.

The Systemic Problem

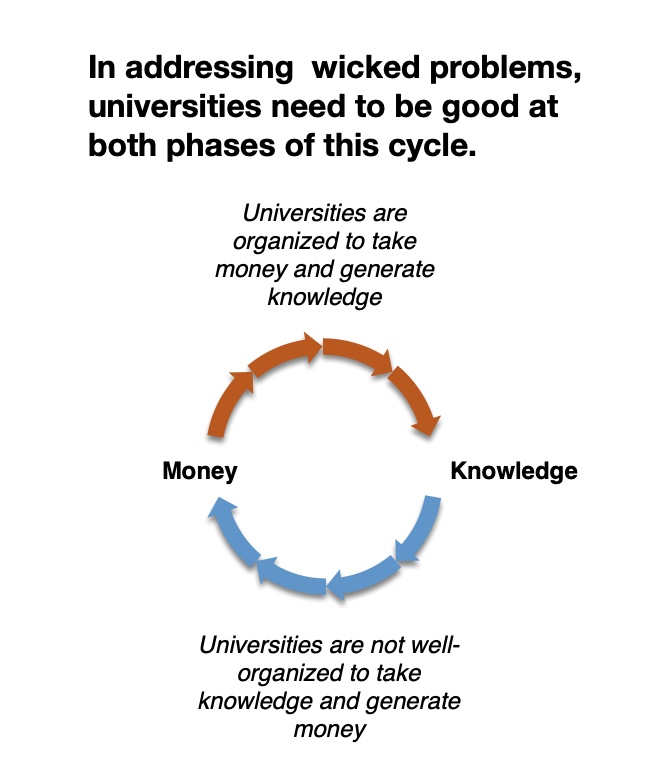

Universities have set up extensive internal systems to take money and generate knowledge. So, universities of any size have mechanisms to gather government and foundation money and generate research.

But here’s what they are not particularly well designed to do: take the knowledge they have and generate money from that knowledge. In other words, they do not do a good job creating value out of the knowledge they generate. To do that, they need to create new organizational designs — new structures — that promote collaboration.

If we are going to generate scalable solutions to our wicked problems, we need to design solutions that are replicable, scalable and sustainable. These solutions must generate value. And that’s not what universities are particularly well-suited to do.

In recent years, universities have focused on improving. They have adopted organizational innovations — incubators, accelerators, venture funds — largely by focusing on entrepreneurial start-ups. They have focused on creating entrepreneurial ecosystems around their campus.

But universities have generally not focused on working with existing companies to solve big problems. In other words, they have neglected their innovation ecosystems. The good news: by adopting a tested organizational innovation from business — becoming platform leaders— they can accelerate quickly to create new innovation ecosystems focused on wicked problems.

Time is getting shorter

Truth, be told, though, universities have not accelerated their evolution to keep pace with our growing challenges. It’s no secret wicked problems have been accumulating. These challenges — climate change, the pandemic, water shortages, food insecurity, and so on — call for a multidisciplinary response: what Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson calls “extreme teaming“.

But extreme teaming — designing and guiding collaborations that cross organizational and political boundaries — is not easy.

Our research universities can lead us to new solutions, if they choose.

To do that, though, universities will need to innovate. Scholarly silos narrow research perspectives at a time we must explore across disciplines.

Here’s the problem in a nutshell: virtually all of the resources and rewards within a university flow vertically. Few incentives encourage cross disciplinary collaboration. Administrators (deans, department heads) learn to protect their boundaries. These attitudes and behaviors stifle collaboration.

There is a path forward. Universities can borrow the idea of platforms to stimulate cross-disciplinary innovation. The good news is that experimenting with a platform-based approach to collaboration is simple and low-cost. Strategic Doing, a strategy discipline for complex networks, provides an operating system that faculty and administrators can learn. Experiments can be measured by a simple metric: how much co-investment do they stimulate?

Since 2015, our Agile Strategy Lab has been collaborating with a global leader in applied research, the Fraunhofer Institutes in Germany. At the same time, we have begun working with universities to explore how they can leverage Strategic Doing to accelerate collaborations both across campus and with potential outside investors. Universities can become platforms for what European scholars have come to call “Open Innovation 2.0“: the development of vibrant ecosystems addressing wicked challenges.

If you are interested in learning more about our work in this area, contact Liz Nilsen: lnilsen@una.edu.

The Founder of the Lab at UNA and co-author of Strategic Doing: 10 Skills for Agile Leadership, Ed’s work has focused on developing new models of strategy specifically designed to accelerate complex collaboration in networks and open innovation. He is the original developer of Strategic Doing.