How to Become Better at Implementation

The US is good at invention but not very good at implementation. We have generated a boatload of Nobel prizes but stumble at the broader challenges of technology adoption and deployment.

Why is that?

THE 75+ YEAR-OLD BLUEPRINT FOR OUR RESEARCH SYSTEM

The reason goes back to the central design of our research system. After World War II, Vannevar Bush created our postwar research economy blueprint. His report Science: The Endless Frontier recommended a clear break between basic and applied research. Leave basic research to universities and applied research to business.

Unfortunately, for various reasons, this simple linear model — separating basic and applied research — doesn’t work very well anymore. Several good books explore the shortcomings (Stokes, 1997; Curral et al., 2014; Narayanamurti & Odumosu, 2016; Shneiderman, 2016).

We can see the gap emerging from two perspectives: the retrenchment of our industrial R&D system (no more Bell Labs, for example) and the nature of academic scholarship (curiosity-driven research and extreme specialization).

But the basic problem is a lack of coordination across the government, private firms, and universities.

We are not collaborating very well.

DIG DEEPER: TECHNOLOGY READINESS LEVELS AND SOCIO-TECHNICAL SYSTEMS

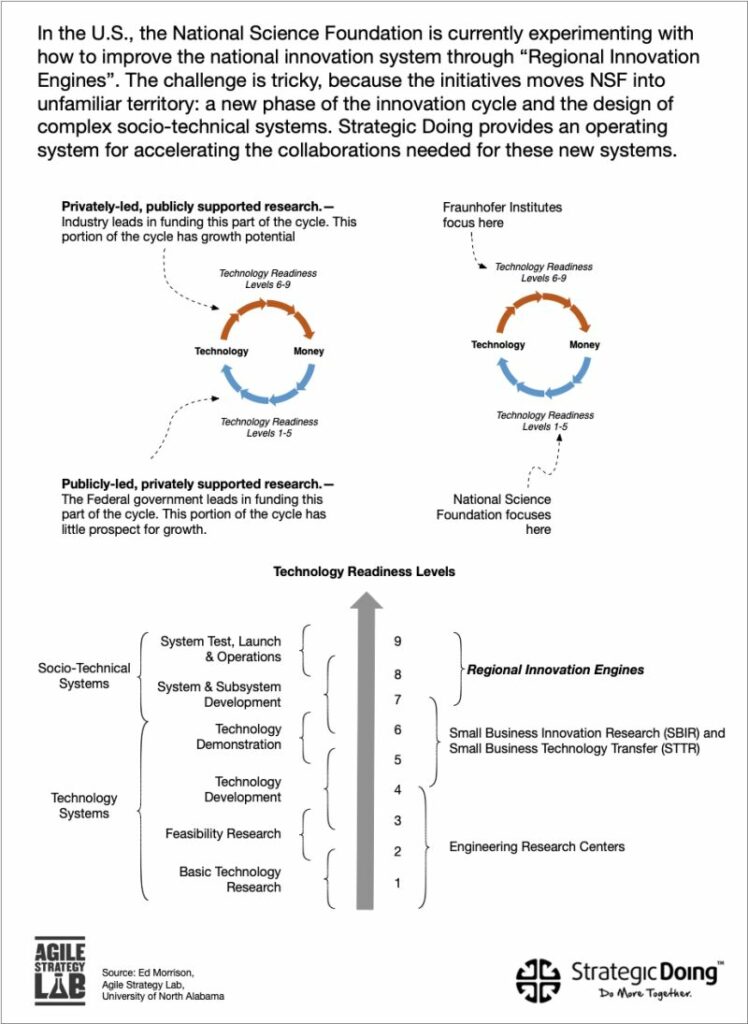

Technology Readiness Levels can help us make sense of the challenge. We’ve designed the early stages of research TR Levels 1-5 very well. We have a robust research system that takes money and generates knowledge (and Nobel prizes).

Where we stumble is in TR Levels 6-9. Here, we get into the design of systems for deploying technology, and it gets tricky.

These are “socio-technical” systems.

In other words, successful technologies are embedded in social systems that must be designed and guided. (When this doesn’t happen, technology can race ahead and cause real damage. Example: investors losing billions on crypto.)

For successful deployment to happen, we need to design new socio-technical systems (emphasis on the SOCIO).

That’s where we are stumbling.

By definition, socio-technical systems are complex. No one organization can design them alone.

To design these new systems, we need to collaborate.

Fraunhofer in Germany provides a model to follow.

In 2013, our small team Purdue collaborated with colleagues from Fraunhofer IAO. We explored this question: how could we design an innovation ecosystem around our research universities that was more privately led and market-driven?

REGIONAL INNOVATION ENGINES

We are starting to see new policy orientations in the National Science Foundation. They recently Initiated Regional Innovation Engines, an effort to focus on the design of these new systems.

How might we design regional innovation systems following market-oriented, Fraunhofer-type principles?

Strategic Doing, provides the open-source operating system for these regional innovation systems.

In the coming weeks, I’ll share how we are approaching these challenges.

The Founder of the Lab at UNA and co-author of Strategic Doing: 10 Skills for Agile Leadership, Ed’s work has focused on developing new models of strategy specifically designed to accelerate complex collaboration in networks and open innovation. He is the original developer of Strategic Doing.